In July 2024, I embarked on an exciting collaboration with Dr Mona Sakr and Kayla Halls at Middlesex University on a Nuffield-funded research project examining the baby room in England. The project, titled Achieving high-quality provision in the baby room of English nurseries, aims to kick start a much needed conversation around what quality provision looks like for children aged 0-2 in English nurseries.

This research comes at a pivotal time in policy, following the government’s expansion of childcare entitlements, announced in March 2023. While the expansion is being rolled out in phases (some of which are already in effect), the full implementation will be complete by September 2025. At that point, all children under five, whose working parents meet the criteria, will be eligible for 30 hours of funded childcare. For the first time in England, this entitlement will extend to children as young as 9 months. This will likely lead to an increase in the number of children that will be in a baby room for part of their day and hopefully prompt greater public scrutiny of the quality of care and education for 0-2-year-olds — a domain that has traditionally been viewed as a private matter in England. You can learn more about the project on our website: https://thebabyroom.blog

The project, which runs from July 2024 to August 2026, is currently in its initial phase. We are conducting a comprehensive review of existing research to identify the key components of high-quality provision and assess the current state of baby room provision in England. Already, the literature has sparked some fascinating discussions within our team. Just last week, Kayla wrote a great blog post summarizing our conversation on the variation in terminology across different countries.

I’m sure this will be a recurrent topic of conversation for us, but a key point relating to our project is that while in England and Australia the term used is ‘babies’ and by that we mean children ages zero to two, in most other countries the terms used are infants and toddlers, where an infant is a child age zero to one year of age and toddler is one to three years old. We could further disaggregate to newborns and remark that some non-English languages follow this same disaggregation. This offers insights not only into semantic differences but also into the varied societal perceptions of babies and young children. Kayla explores this in more depth in her blog.

These terminological distinctions have practical implications for data collection. In England, publicly available data on babies in out-of-home care — our project’s focus — only covers children aged 0-2 as a single group. There is no data disaggregating the numbers or proportions of children under one year old, compared to those aged 1-2. Yet, as any parent or practitioner will confirm, there are significant developmental differences between these two age groups, and even between babies just a few months apart.

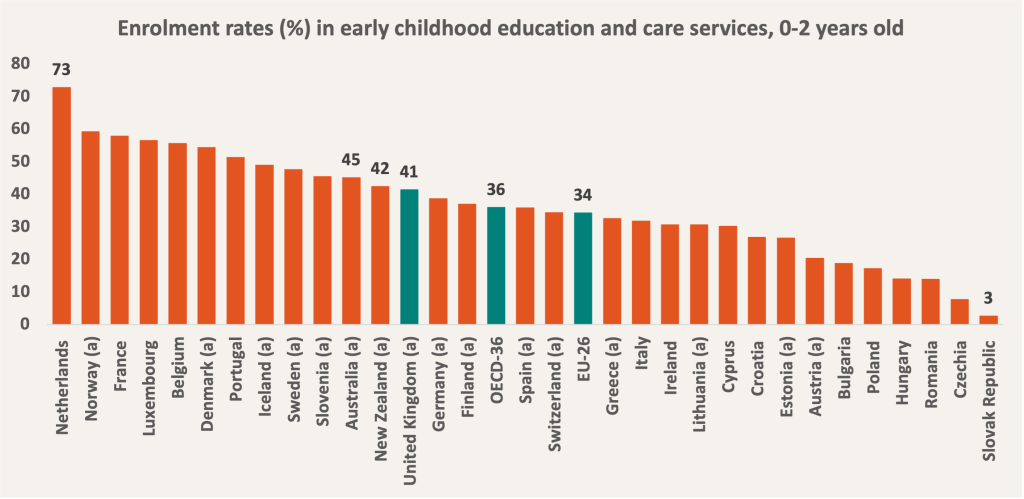

I went down a rabbit hole trying to find disaggregated data and even at international level it is difficult. The most relevant data I found was the data in the chart below, which shows that across the OECD, on average 36% of children ages 0 to 2 were enrolled in ECEC in 2022, albeit with a significant variation by country, from 70% (the Netherlands) to less than 10% (Czechia and Slovak Republic).

Source: OECD Family Database, Chart PF3.2.A. Enrolment rates in early childhood education and care services, 0- to 2-year-olds

(a) Data for Iceland the United Kingdom refers to 2018; for Australia, Austria, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Lithuania, New Zealand, Norway, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden and Switzerland to 2021

One important caveat to keep in mind is that the OECD data is UK-wide. Finding England only data was even trickier. The most recent data only focuses on children 0-2 aggregated and only on those children who are in receipt of an entitlement. I had to go back to pre-Covid-19 times to be able to find some disaggregated data.

Use of childcare, by age of child

| Age of child | ||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 0-2 | |

| Use of childcare | % | % | % | % |

| Any childcare | 32 | 62 | 71 | 61 |

| Formal providers | 11 | 36 | 57 | 41 |

| Informal providers | 24 | 43 | 35 | 37 |

| No childcare used | 68 | 38 | 29 | 39 |

Source: Table 1.6 Use of childcare providers by children (by age of child). Childcare and early years survey of parents 2019

I’ve always thought that which data is made publicly available is very telling on where the government wants the focus to be. In the past 5 years, there seems to have been little interest in having a more granular picture of how ECEC services are used by children under two. I am sure that the entitlement expansion will bring greater interest and more granular data collection.