I’ve been pondering for a while about which topic to prioritize on this website. Then I realized, instead of overthinking, I should just start with something familiar. And what’s more familiar than your family’s language?

Like many families, we speak more than one language at home: English and Italian. I learned other languages later in life (I wouldn’t say I became fluent until I started living abroad as a young adult). My husband, a native English speaker, never learned a second language growing up — he only started learning Italian when we had our daughter. Our daughter is bilingual. This illustrates how our experiences with language vary, shaped by the countries and contexts we grew up in. Different approaches, different nuances and different connotations.

But does that make us ‘different’? Not really. According to the World Atlas of Languages, there are over 8,000 languages documented worldwide, with around 7,000 still actively spoken or signed. Yet, in England, speaking more than one language can make you feel ‘different,’ especially when you are labelled under the term commonly used to describe children in the school system who speak English as a second (or third) language: English as an Additional Language (EAL). It carries a different vibe from the term bilingual, doesn’t it?

Grammatically, how do we even use EAL in a sentence? Do we have EAL? It’s not an illness or condition. Are we EAL? Or are we people who speak or use EAL? Thankfully, there’s been progress in how this term is understood. For example, I have always appreciated the way that The Bell Foundation discusses EAL and multilingual support.

From a statistical perspective, am I someone who uses EAL? Many people use English more often than their mother tongue. I don’t think of English as an ‘additional’ language. What about my daughter? She’s classified as EAL, even though she is perfectly fluent with a strong British accent. Does that label really apply to her? Research has increasingly shown that simply labelling someone as “EAL” offers little insight into their actual situation and educational needs.

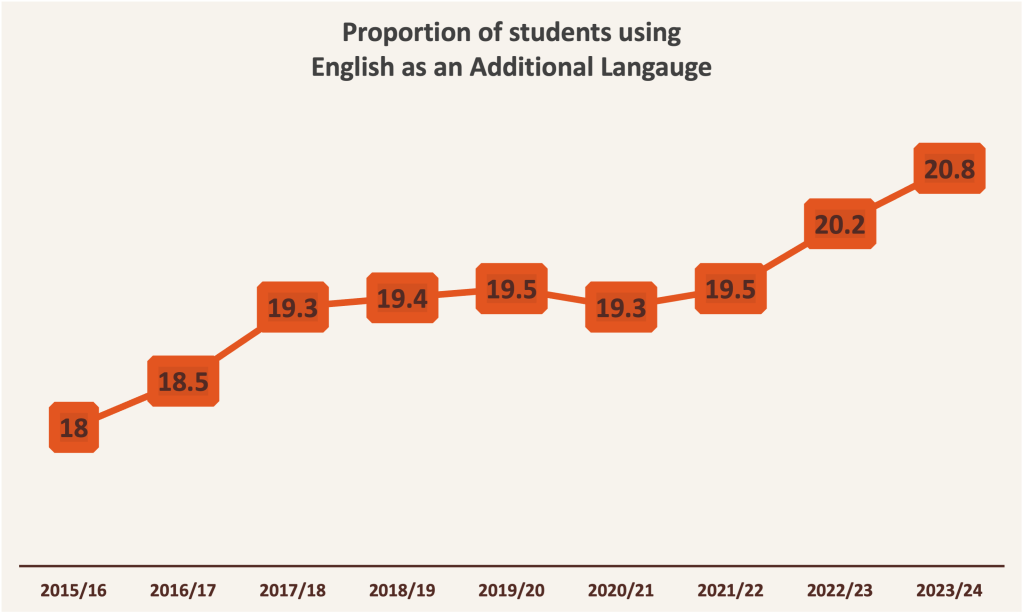

The EAL label can make it seem like speaking English in addition to another language is an exception or a rarity. Yet, the proportion of children in English schools classed as EAL has been steadily rising over recent years.

More importantly, monolingualism is not the norm; multilingualism is a reality for most people in the world. In fact, it’s often an advantage, depending on how it’s approached. It my experience, the tendency to categorize people as speaking a language ‘in addition’ to the dominant one in their country – often with a deficit-based approach – is prevalent in Anglo-Saxon countries, where an English-centric worldview is common. I much prefer a strength-based perspective, one that embraces the richness and of multilingualism.