When we talk about graduates in early years education, the conversation often stops at “how many do we have?” But the real question is just as much about where they are — and who gets access to them.

Why Graduate Distribution Matters

Evidence shows that degree-qualified early years educators can make a measurable difference for children’s outcomes — particularly for those from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Yet, in England, the children who stand to gain the most are often the least likely to benefit.

Graduates are disproportionately concentrated in maintained nurseries and schools, while private, voluntary, and independent (PVI) settings — which serve the majority of disadvantaged families — have fewer graduates on staff.

This imbalance risks widening inequalities rather than narrowing them.

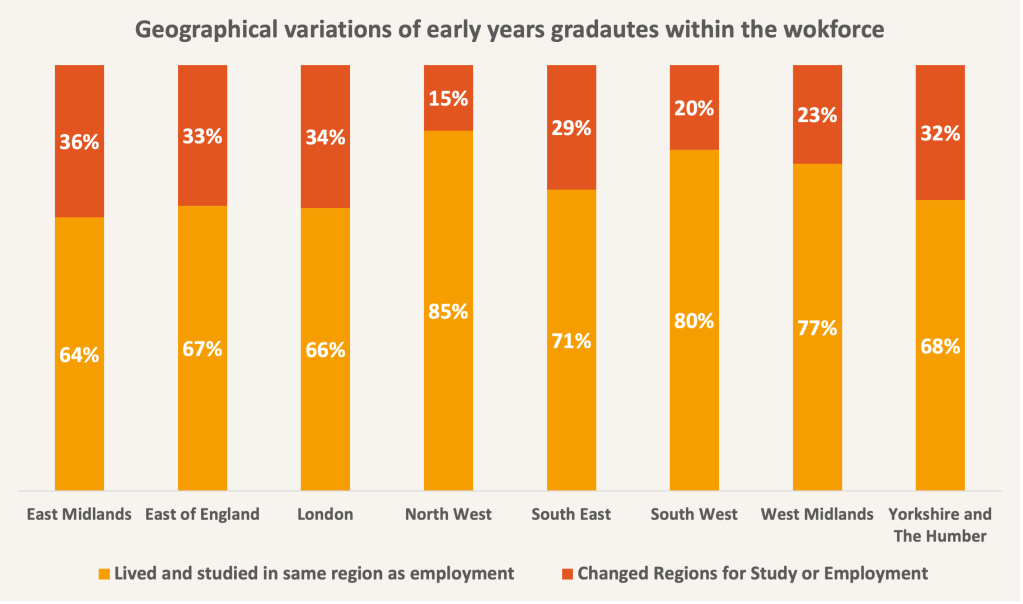

What the Data Shows

In a report I co-authored with Verity Campbell-Barr in 2020, we examined the graduate early years workforce and found some striking patterns:

Localised training and employment

- 79% of early years students studied within 50km of their pre-university home.

- 92% returned to work near where they grew up.

- 77% of graduates remained within 50km of their study location.

Unequal distribution of courses

- Teacher training courses (EYITT, EYTS, and degree programmes) are unevenly distributed across England.

- Areas without nearby provision are far less likely to develop a strong graduate workforce.

The impact

The combination of limited mobility and patchy training provision creates a highly unequal geography of graduate presence. In practice, this means:

- Some local authorities can rely on a steady pipeline of graduates.

- Others, often in disadvantaged regions, are left with few.

- Children’s experiences — and opportunities — vary sharply as a result.

International Lessons

New Zealand — uses equity funding to support providers in disadvantaged areas to employ graduates, tying CPD and pay supplements to progression.

Denmark — graduate pedagogues are standard across childcare settings, embedded through funding streams and professional frameworks.

Italy — integrates graduates into the 0–6 system as pedagogical coordinators, ensuring expertise is evenly distributed.

These models show that distribution is not an accident — it’s a policy choice.

England’s Challenge

The Best Start in Life Strategy commits to growing the graduate workforce, particularly through EYITT and EYTS routes. But without tackling distribution, two risks remain:

- Graduates cluster in advantaged areas and settings.

- Financial incentives alone won’t drive graduates into disadvantaged areas unless matched with status, pay parity, and clear career pathways.

Where Next?

If we want every child to benefit from graduate-led provision, we need:

- Targeted funding — salary supplements or bursaries for graduates in disadvantaged communities.

- National workforce planning — to align course provision with areas of greatest need.

- Parity and progression — so early years graduates aren’t choosing between staying in the sector or pursuing QTS for better pay.

Because right now, unequal distribution of graduates = unequal opportunities for children.